Leafhopper – Pest

Leafhoppers feed on many different fruits, vegetables, flowers, and woody ornamental hosts. Most species of leafhoppers feed on only one or several closely related plant species. Adults mostly are slender, wedge-shaped, and less than or about equal to 1/4-inch long. Leafhoppers generally are varying shades of green, yellow, or brown, and are often mottled. Some species are brightly colored, while others blend with their host plant. Leafhoppers are active insects; they crawl rapidly sideways or readily jump when disturbed. Adults and nymphs and their pale cast skins are usually found on the underside of leaves.

Identification

Leafhoppers may sometimes be confused with aphids or Lygus bugs. Look for leafhoppers or their cast skins on the undersides of affected leaves. Look at their actions; they are faster than aphids and run sideways and jump. Lygus bug nymphs are light green and also move much faster than aphids. They can be identified by their red-tipped antennae. Aphids can be distinguished by two tubelike structures, called cornicles, protruding from the hind end. One or more long rows of spines on the hind legs of leafhoppers and characters on their head distinguish leafhoppers from most other insects they resemble.

Some common leafhopper species in gardens and landscapes. The common leafhopper found on plumeria is the potato leafhopper.

Life cycle

Leafhoppers go through incomplete metamorphosis in their development. Female leafhoppers insert tiny eggs in tender plant tissue, causing pimple-like injuries. Overwintered eggs begin to hatch in mid-April. Wingless nymphs emerge and molt four or five times before maturing in about 2 to 7 weeks. Nymphs resemble adults except that they lack wings; later-stage nymphs have small wing pads. There is no pupal stage. Leafhoppers overwinter as eggs on twigs or as adults in protected places such as bark crevices. In cold-winter climates, leafhoppers may die during winter and in spring migrate back in from warmer regions. Most species have two or more generations each year.

Leafhoppers go through incomplete metamorphosis in their development. Female leafhoppers insert tiny eggs in tender plant tissue, causing pimple-like injuries. Overwintered eggs begin to hatch in mid-April. Wingless nymphs emerge and molt four or five times before maturing in about 2 to 7 weeks. Nymphs resemble adults except that they lack wings; later-stage nymphs have small wing pads. There is no pupal stage. Leafhoppers overwinter as eggs on twigs or as adults in protected places such as bark crevices. In cold-winter climates, leafhoppers may die during winter and in spring migrate back in from warmer regions. Most species have two or more generations each year.

Damage

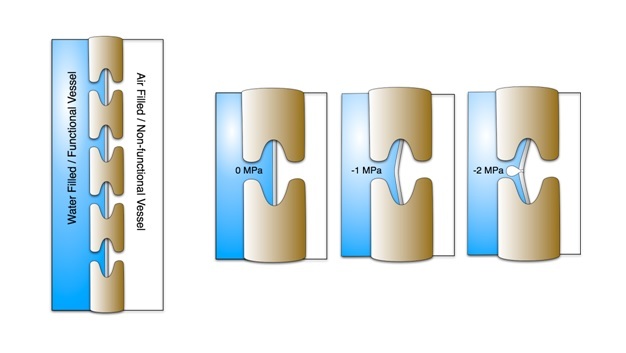

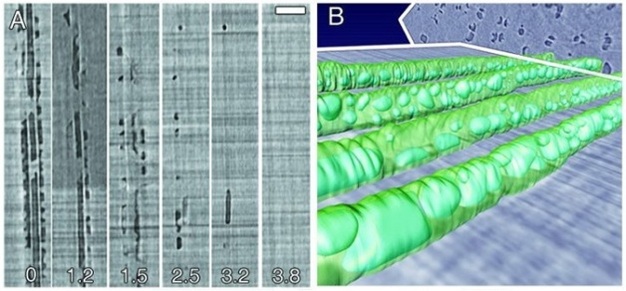

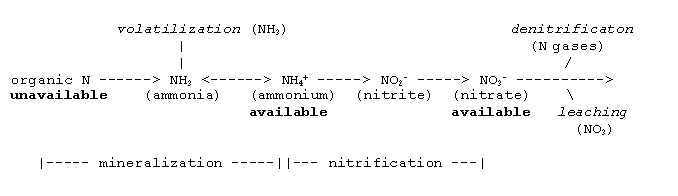

The potato leafhopper has a sucking mouthpart that it uses to pierce into the vascular tissue of the plant and feed on the plant juice, sapping it of nutrients.

However, according to Groves, the damage is most commonly seen on the plumeria as a result of a condition called hopper-burn, which is the plant’s physiological response to the leafhopper’s saliva. The saliva causes the vascular system to be disrupted, and the leaves that have been fed on curl up and can become necrotic.

Leafhopper feeding causes leaves to appear stippled, pale, or brown, and shoots may curl and die. Black spots of excrement and cast skins may be present on leaves. Some leafhopper species transmit plant diseases, but this is troublesome mostly among herbaceous crop plants.