A Guide for Growing Plumeria From Seed by Tex Norwood

This guide shares the basic methods I use for growing plumeria from seed, caring for seedlings, and the products I use. I hope this guide helps you with your seed goals for the year.

There are many proven methods to growing plumeria from seed and you should examine to see if any could help you develop a method that works for you. This is only a guide and should be adjusted to your seed growing environment.

When I have a batch of seeds, I examine what I did in the past and determine if I can make any improvement. The following is my detailed plan for growing plumeria from seed in 2018. This plan covers from germination until they first produce blooms.

Please keep in mind your growing environment and the differences from South Florida Zone 10B. The start of your plan should correspond to when you are past the threat of a frost or freeze. You should also make plans to protect your plumeria from cold weather, just in case you have a late freeze or frost.

My goal is to know what, when, and why, so I can improve my method every year or even with each batch. Documenting all adjustments as you go will allow you to look back and better determine where you can make improvements.

Why do I grow seedlings?

1. To grow new and exciting cultivars

2. To grow rootstock for grafting

3. But most of all to see that one-of-a-kind flower for the first time.

Using the methods and products below; I have been able to get about 10% of my seedlings to bloom in less than 12 months and about 60% to bloom in 18 to 24 months. The majority of the remainder bloom from 24 to 36 months. (Some do still take 3 years and even longer.)

What you will need: Plumeria Seeds, something to soak them in, paper towels, 2” x 3” Gro-Tech FlexiPlugs and trays or plugs or good seedling soil mix to plant the seeds in, Vitazyme, Carl Pool’s Root Activator, Bioblast 7-7-7, Pro-Mix BX Mycorrhizae, Excalibur VI 11-11-13, Labels and permanent felt tip marker. Hydrogen Peroxide is good to use for mold or fungus.

Seed selection

Seed selection is very important when growing plumeria seeds. Plumeria Rubra seeds do not produce true to their parents. Sometimes a seedling will look like its parent, but it will never be exactly the same. A few characteristics to consider:

- Flower: Color, size, keeping quality (how long it lasts after picking), fragrance, etc.

- Tree: Growing habit, size, etc.

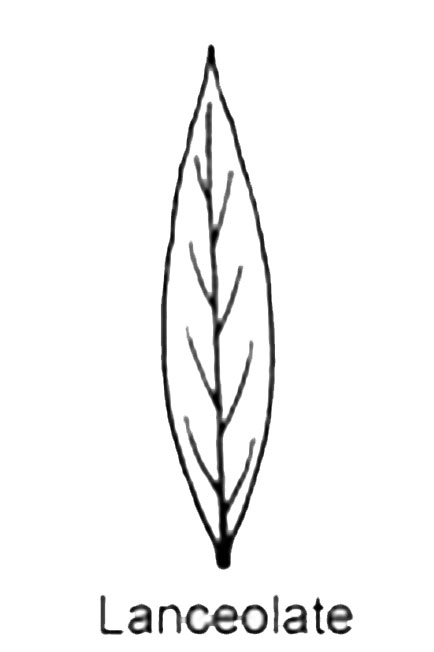

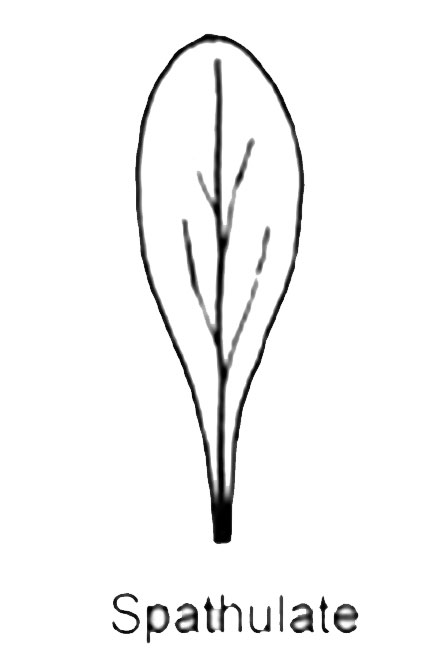

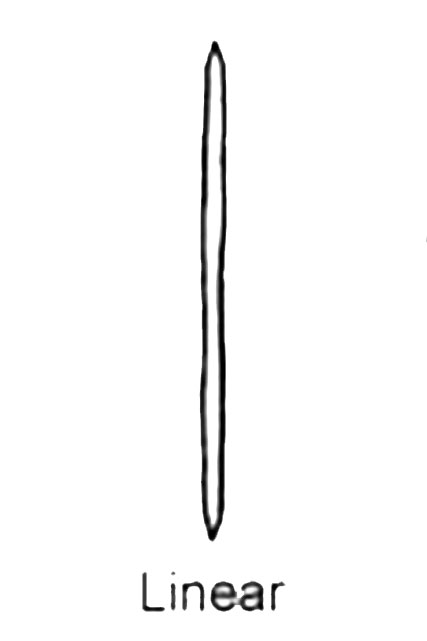

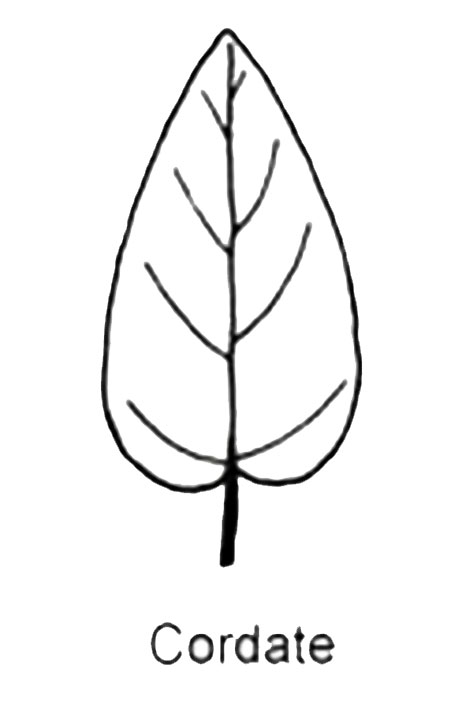

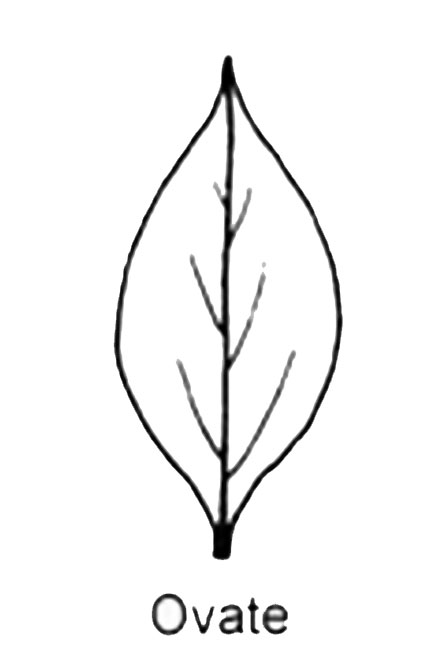

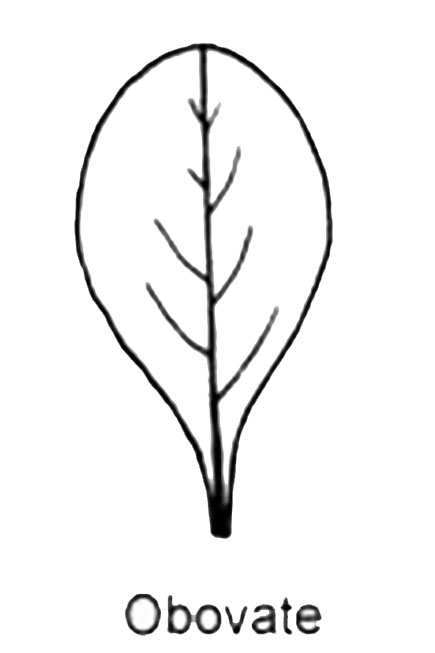

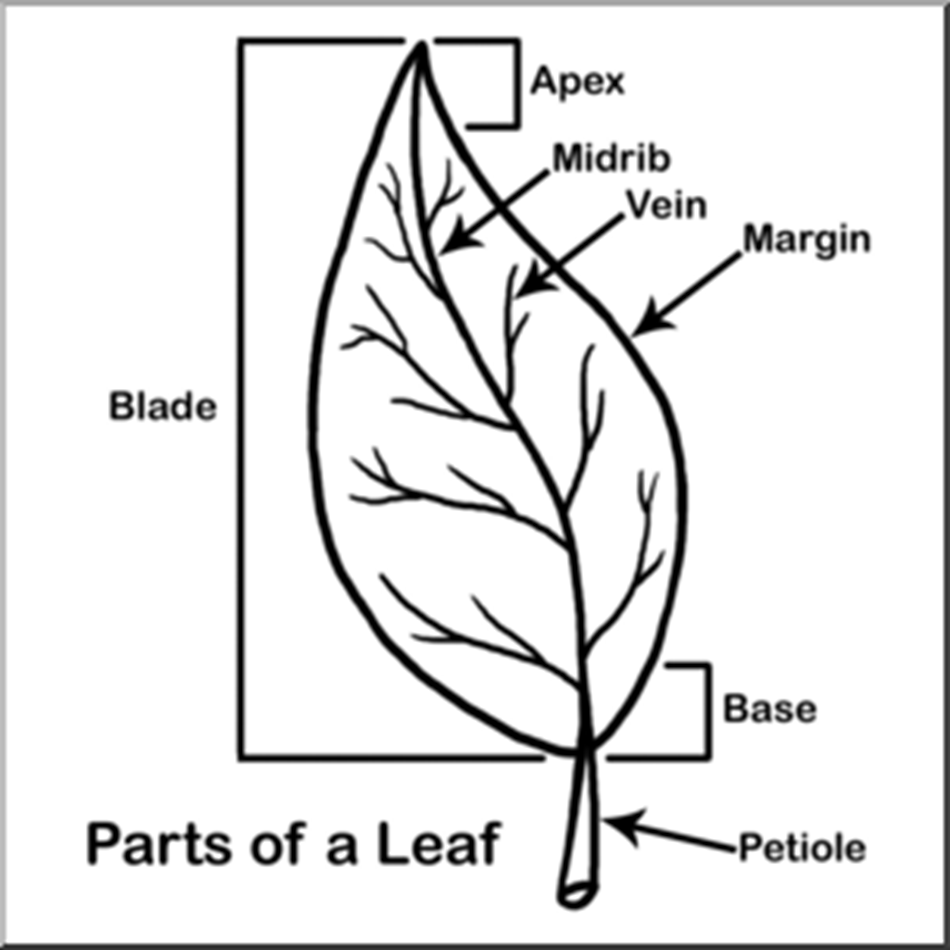

- Leaves: Color, size, etc.

- Blooming: Quality, size of inflorescence/flower stalk, number of flowers blooming at the same time, how long does it bloom, etc.

I’m always trying to improve my chances of getting that spectacular plumeria seedling.

If possible:

- Select a pod parent that is known to produce the characteristics you desire or at least a pod parent that has the characteristics you desire.

- Obtain seeds from trusted growers.

- Find out the history of the pod, e.g., What’s growing close to the pod? Did they bloom at the same time? Was it cross-pollinated, manually pollinated, or pollinated by nature?

- Obtain all the seeds from a pod when possible.

- Select seeds from a healthy tree.

- Select seeds that are plump and look healthy.

Before you plant your seeds

Soak plumeria seeds to test the viability and soften the shell to give them a kick start.

When: Plumeria seeds germinate best in the spring, but can be germinated any time if provided with enough moisture and warmth staying above 60 degrees.

What: Use quality seeds, warm water, and Vitazyme

How:

- First, examine each seed by placing it between two fingers. If they have some thickness, they most likely are viable. If they feel paper-thin, they most likely are not viable.

- For faster germination and rooting, dilute Vitazyme with warm water at a rate of 1 oz to 19 oz of water, a 5% solution, and dip or mist both sides of the seed. Allow seeds to dry prior to planting or soaking.

- For a soaking mixture, dilute Vitazyme with warm water at a rate of about 1.29% or 1 oz to 128 oz (1 gallon).

- Place your seeds in the container, place in a warm area, and allow to soak for approximately 4-6 hours (or even overnight). Soaking longer than overnight could cause damage to the seeds. Seeds that are very thin and are still floating are most likely not viable. To further test this, plant all the seeds, but mark the ones that did not sink.

- Check your seeds after several hours to see which seeds are absorbing enough liquid to allow germination and to sink to the bottom.

- Do not allow your seeds to dry out before you plant them.

- Now your seeds are ready to plant.

Why:

- To soften the seed’s protective coating

- To allow the seed to absorb as much water as possible

- To test the viability of the seed

- To provide nutrients as early as possible, helping germination and starting the rooting process sooner

Preparing Plugs

When: Prior to planting seeds in plugs.

What: 2”x3” Grow-Tech peat plugs, warm water, Root Activator, and Vitazyme.

What we suggest: A mixture of warm water, Vitazyme, and Carl Pool’s Root Activator.

How: Soak your plugs in a mixture of 1 gal of warm water, 2 oz Root Activator, and 1 oz Vitazyme for about 2 hours.

Why: Vitazyme is a bio stimulate with vitamins that help the overall health of the seeds and the Root Activator adheres to the plugs or soil and gives the roots a kick-start. I use the plugs because they hold the right amount of moisture and provide ample aeration that allows the new roots to breathe.

Watering: Keep your plugs wet or leave them soaking until you are ready to plant the seeds.

Planting your seeds

When: Plant your seeds right after soaking into the prepared plugs. DO NOT allow either to dry out. If they dry out they could be damaged.

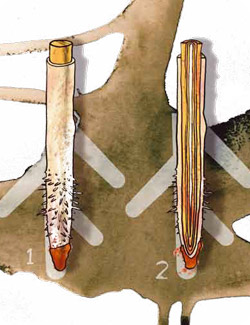

Plugs, Pots, or Trays, After Soaking, For the seeds, I grow for new cultivars, I prefer planting the seeds directly into 2″ x 3″ Grow-Tech FlexiPlugs, a foam peat plug. For the seeds, I’m growing for rootstock in flat trays or 4″ pots.

What: Carefully selected plumeria seeds, 2”x3” Grow-Tech FlexiPlugs. Warm water, Root activator, and Vitazyme. You will also need a 36-hole tray and a flat for the plugs. A cover is optional.

Why: The reason I use the plugs is they hold moisture allowing me to keep them soaked with water and still providing ample aeration and allowing the new roots to breathe. I use the 2” x 3” FlexiPlugs that allows me up to 14-21 days before I have to transplant to pots.

Watering – I grow Plumeria seeds in full sun and water 2-3 times a day depending on the weather. My goal is to keep the plugs very moist to the touch. I have had no damping off or rotting problems with this method.

Start Fertilizing – Foliage

When: Before transplanting the plugs into pots, after three or four true leaves have grown. I use the same mix ( see below) approximately every two weeks

What: BioBlast 7-7-7 NPK fertilizer, Vitazyme

How: Foliar feeding early in the morning or late in the evening with Bioblast at 1 tablespoon per 1 gallon of water and Vitazyme at 1 tablespoon per gallon. Do not spray in the hot sun it will burn the seedling leaves.

Why: Seedlings have seed leaves that provide them with nutrients for the first few weeks of their life, but when the seed leaves dry up and fall off the seedling needs nutrients. Bioblast works with every part of your plant. Soil organisms are invigorated with Vitazyme bio-stimulants providing quicker, more vigorous growth. Roots are encouraged with our Root Activator. A balanced 7-7-7 NPK provides the essentials of plant growth and structure. B-Vitamins and Zinc encourage a robust immune system, while Iron promotes chlorophyll production in the leaves.

Watering – I continue to grow Plumeria the seedlings in full sun and water at least 2-3 times a day depending on the weather. My goal is to keep the plugs moist to the touch. I’ve had no damping off or rotting problems.

Transplanting to Pots and Fertilizing

When: As soon as I see roots sticking out of the plugs , transplant into larger pots. Normally I will use 1 gal pots, but this year I’m using 7.5 gal squat pots. Approximately 14 days after planting in the plugs.

, transplant into larger pots. Normally I will use 1 gal pots, but this year I’m using 7.5 gal squat pots. Approximately 14 days after planting in the plugs.

What: ProMix BX Mycorrhizae, Excalibur VI 11-11-14 with micronutrients, Vitazyme, and Root activator.

How: Fill 1 gal. pot with a mixture of ProMix BX Mycorrhizae mixed with 2 tablespoons of Excalibur Vi. Fill a 7 1/2 gal. squat pot with ProMix BX Mycorrhizae or the mix of your choice, dig an area our in the mix about the size of a 1 gal pot, port the contents of the 1 gal pot in the hole, then punch a hole about the size of the FlexiPlug (about 2″x3″) in the center of the filled 7 1/2 gal pot. Place the plug in the hole and press the mix firmly around the plug. Water in well with a mix of Vitazyme 1 oz to 1 gal and Root Activator 2 oz to 1 gal. You may need to add more soil mix if the plug is not covered completely with at least ½” of the mix. Water again the next day and then when the soil is almost dry. I would suggest using a water meter from time to time to verify the moisture content. It is very important the soil does not stay wet.

Why: Promix BX contains Mycorrhizae and is a fast-draining mix. The Excalibur VI, a 6-month granular slow-release fertilizer designed specifically for plumeria that provides all the nutrients a seedling needs to grow strong. Vitazyme a bio-stimulate helps the overall health of the seedlings and the Root Activator adheres to the soil and is there to help the roots develop and grow faster.

Watering – Water once a day for the first two days, then water when the soil is barely moist. At this point, I check with a moisture meter and water when on the low side of moist. It is important not to overwater, keeping the excess soil mix from becoming water-soaked. It is also important not to allow the root zone to become dry.

Fertilizing – Throughout the growing season

When: Apply Excalibur VI every six months, Foliar feed every two weeks to every month with BioBlast.

What: Excalibur VI 11-11-13, BioBlast 7-7-7, Vitazyme and Carl Pool’s Root activator

How: After 6 months, I spread 3 or 4 tablespoons of Excalibur VI on the top of the soil and mix in the top 1-2” of the soil. The seedling should still be in the 7 1/2 gal squat pot. Foliar feed with BioBlast 1 oz to 1 gallon and Vitazyme 1 oz to 1 gal every month or less. Drench with Vitazyme and Root Activator in the Early Spring or if transplanting.

Why: Excalibur provides a balanced slow-release fertilizer specifically designed for plumeria. BioBlast works with every part of your plant. Soil organisms are invigorated with Vitazyme bio-stimulants providing quicker, more vigorous growth. Roots are encouraged with our Root Activator.

If possible, do not let seedlings go dormant their first winter. You can treat seedlings as adult plumeria after the first growing season.

Keep looking for more space, they will grow!

As mentioned, the root system will only increase in volume for as long as the rest of the plant continues to grow. However, transpiration from the leaves can also cause more roots to form in order to pump up the water needed. In the end, an equilibrium is established between the roots and the plant. A general rule of thumb is that the root system should comprise 30% of the total plant volume. Although this rule applies fairly consistently to plants in the open air, in substrate culture this does not always have to be the case. You can grow large plants in small pots as long as you supply them with water and nutrients and do not allow the pot to get too dry or too wet. To reduce the chance of this happening, we advise a large medium volume.

As mentioned, the root system will only increase in volume for as long as the rest of the plant continues to grow. However, transpiration from the leaves can also cause more roots to form in order to pump up the water needed. In the end, an equilibrium is established between the roots and the plant. A general rule of thumb is that the root system should comprise 30% of the total plant volume. Although this rule applies fairly consistently to plants in the open air, in substrate culture this does not always have to be the case. You can grow large plants in small pots as long as you supply them with water and nutrients and do not allow the pot to get too dry or too wet. To reduce the chance of this happening, we advise a large medium volume.